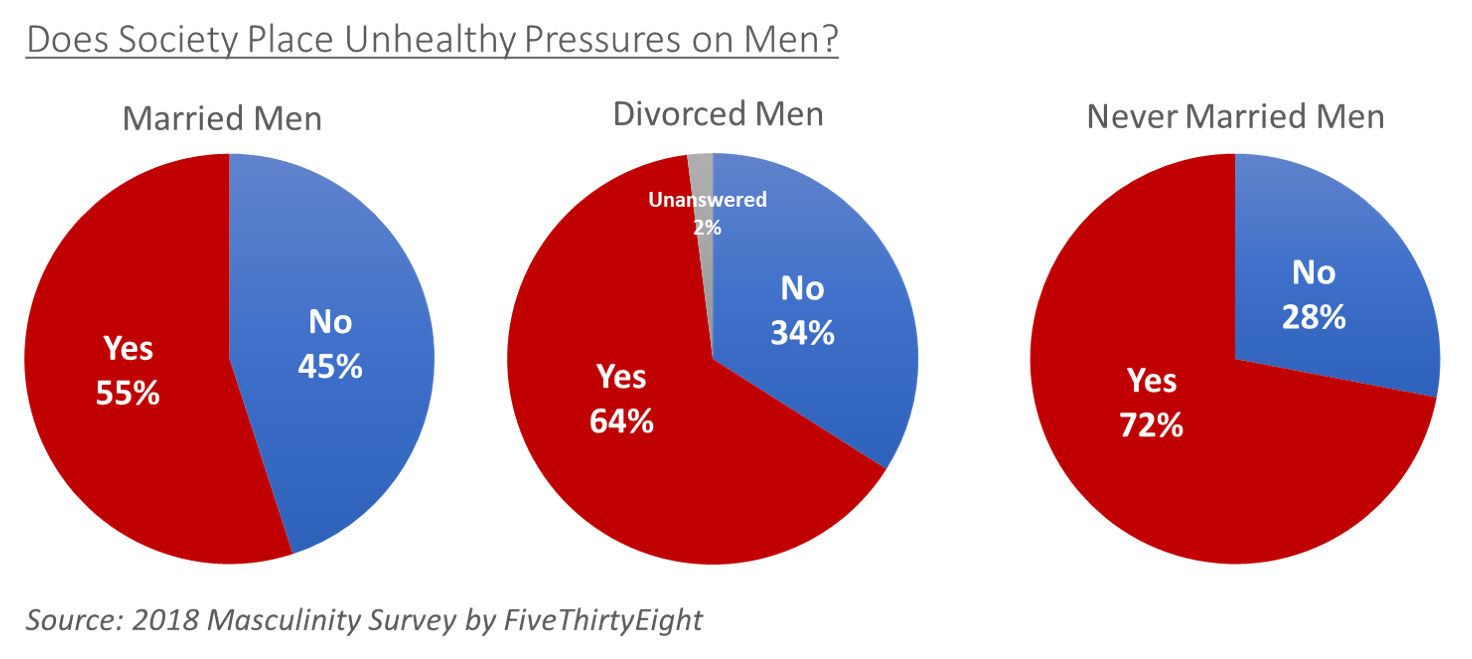

Survey data also suggested that relationship status may play a significant role in how men perceive modern masculinity. About 70 percent of unmarried men said that they thought that society placed unhealthy pressures on men, compared to just over half of married men.

Dr. James Messerschmidt, chair of the criminology department at the University of Southern Maine and author of numerous books and articles on masculinity, said that fulfillment of societal expectations may partially explain this gap.

“Married men feel successful in society because it’s still something that a man is expected to do,” said Messerschmidt. “Married men are conforming to these societal expectations, so they would naturally feel better about them.”

Scott Hochman said that he has encountered these subtle pressures to get married and have children, but noted that their source is different than that experienced by past generations.

“They don’t necessarily come from your family anymore,” said Hochman. “Now they come from your peers through social media … You look at that person with a happy family and a baby on the way and say, ‘why don’t I have those things?'”

Hochman said he is happily single and doesn’t necessarily want children in the future. Some young men, however, are less content being long-term bachelors.

Messerschmidt raised the case of the involuntary celibates, or “incels,” as an extreme example of how men unable to find a partner can become disenfranchised with society. Incels, who are classified as a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center, define themselves as men unable to find romantic or sexual partners despite greatly desiring one. They are known for their violent, misogynistic and self-loathing tendencies and have either perpetrated or inspired several mass killings. Two of the most well-known killings directly attributed to incels are the 2014 Santa Barbra shooting and the 2018 Toronto van attack.

Despite the worrying cases of some extremist groups, Messerschmidt is cautiously optimistic about the future. He described a growing “diversity of masculinities,” which could allow men greater choice in how they define themselves as a man.

“There’s a much broader range now — from incels and white supremacists, to men that are very respectful and don’t want subordinate other men, and everything in between,” said Messerschmidt. “We’re in a period of transition. I just hope society will move towards that latter type.”