The less it rains, the less polluted water drains into the ocean, experts say. It’s perhaps the only benefit to California’s historic drought conditions.

Water quality at California beaches improved last year, according to an annual report card compiled by Heal the Bay, a non-profit that advocates for the health and safety of coastal waters and watersheds. The report found a 10 percent cumulative increase in A and B grades among the 450 sites surveyed, meaning that a higher percentage of beaches are considered safe and sanitary.

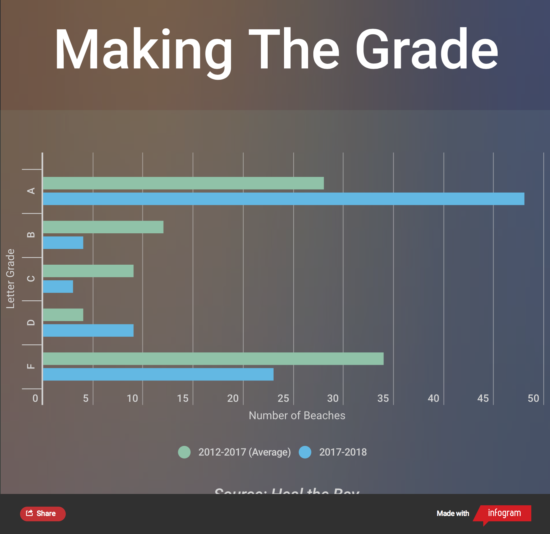

Los Angeles County beaches reflected the statewide trend. In fact, the number of beaches with A ratings nearly doubled this year compared to the past five year average. This graph compares the grades given to the 90 county beaches surveyed between 2012 and 2017 to grades given between 2017 and 2018.

“We’ve been seeing an increase in water quality for quite a while. We do attest it to dry weather and reduced urban runoff.”

While one would assume that a cleaner ocean means nothing but great news, there’s a catch. Ryan Searcy is a Beach Water Quality Modeler for Heal the Bay who runs NowCast, a system of statistical models that use environmental conditions to predict water quality on a day-to-day basis. This data, along with local public health agencies’, forms the Beach Report Card.

This year’s enhanced water quality was not a surprise to Searcy and his colleagues but rather the latest development in a broader trend.

“We’ve been seeing an increase in water quality for quite a while,” he said, “We do attest it to dry weather and reduced urban runoff.”

This fall, Los Angeles County voters will have the chance to establish a potential solution. In part, the Safe Clean Water Program would enhance the county storm drain system by capturing more rainfall to store, clean and reuse to help protect local lakes, rivers, streams, beaches and the ocean from contamination. If passed, the program will be funded by a 2.5 cent parcel tax would only apply to impermeable areas such as concrete roofs and sidewalks. According to the measure’s website, it will raise an estimated $300 million per year.

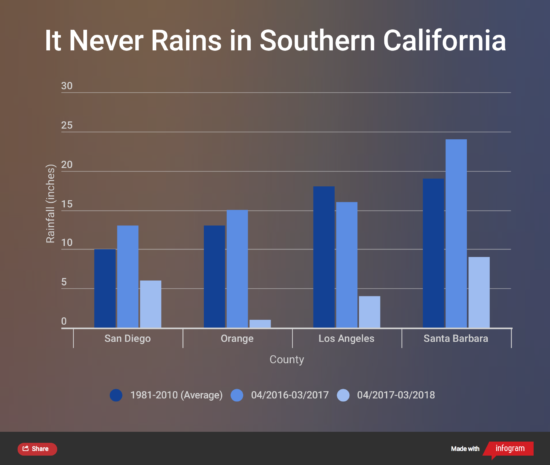

Just how dry is LA? According to Heal the Bay’s count, Los Angeles County received 4.27 inches of rain between April 2017 and March 2018. This figure is not only well below the five and ten-year averages for the region but it also accounts for a measly 25% of the rain received just last year. The chart below compares current and historic rainfall in Los Angeles to the other coastal Southern California counties.

[ezcol_1half]

[/ezcol_1half]

[ezcol_1half_end]

[/ezcol_1half_end]

Although the drought is no longer in the state of emergency, it could still cause considerable damage. Steven Phillips is a hydrologist with the U.S. Geological Survey California Water Science Center. He says that droughts pose a number of environmental threats beyond dry weather.

“There are many environmental effects related to drought including increased fire hazard and post-fire hazards such as landslides,” Phillips said, “Also, the decreased availability of surface water supplies causes increased groundwater use, which draws more water from streams, further decreasing flows and stressing habitat for many species. It can also cause subsidence of the land surface, affecting infrastructure and potentially environmental resources.”

With rain comes runoff, reinvigorating the land but contaminating the ocean.

“The rain itself is not directly impacting water quality, what’s really happening is that all of the buildup of trash and fecal matter and whatever else that you can imagine is building up on our streets inland eventually washes down our flood control system out to the ocean,” Searcy said. “This is a good thing because it prevents flooding in our neighborhoods and property damage but as a consequence, it does have a pretty big impact on our water quality.”

The Santa Monica Pier represents the dangers of mismanaging urban runoff. The water surrounding the pier consistently receives D and F grades due to its proximity to the city’s main storm drain repository. Heal the Bay estimates that just one inch of rainfall in Los Angeles can thus result in billions of gallons of polluted runoff entering the Santa Monica Bay.

USC senior Jake Simpson moved to Los Angeles just three years ago but has already observed Santa Monica’s water quality visibly decline.

“I’ve noticed a lot more trash floating around the pier, even for LA,” he said, “The pollution definitely keeps me from wanting to go swimming there.”

Excessive drainage poses an additional threat besides the degradation of the ocean itself. With pollution comes bacteria and, according to Heal the Bay, beachgoers who come in contact with polluted waters have a much higher risk of contracting illnesses such as ear infections, upper respiratory infections, skin rashes and the stomach flu.

Still, Searcy says that popular beaches such as Santa Monica will never have pristine grades.

“Overall, water quality is likely to be better in areas of less urban population and that correlates to developed watershed, concrete increased runoff during rain,” Searcy said, “Also there’s just more people coming to LA beaches and using them so there are a lot more complex dynamics than a place maybe in the northern parts of the state where there’s a smaller population.”

Granted that Los Angeles receives the rain it needs, an efficient storm drain system such as the one proposed by the Safe Clean Water Program could be the key to sustaining the coast’s repairing health.

“In theory, it’s going to do a really good job,” he said, “Measures like that are really important to reducing the runoff that is created because of this essentially impermeable skin that we’ve placed on our lands and capturing that water rather than letting it run out.”