Reaching space: USC Rocket Propulsion Laboratory breaks world record

USC RPL is the first student rocketry group to design and build a rocket that successfully soared to space.

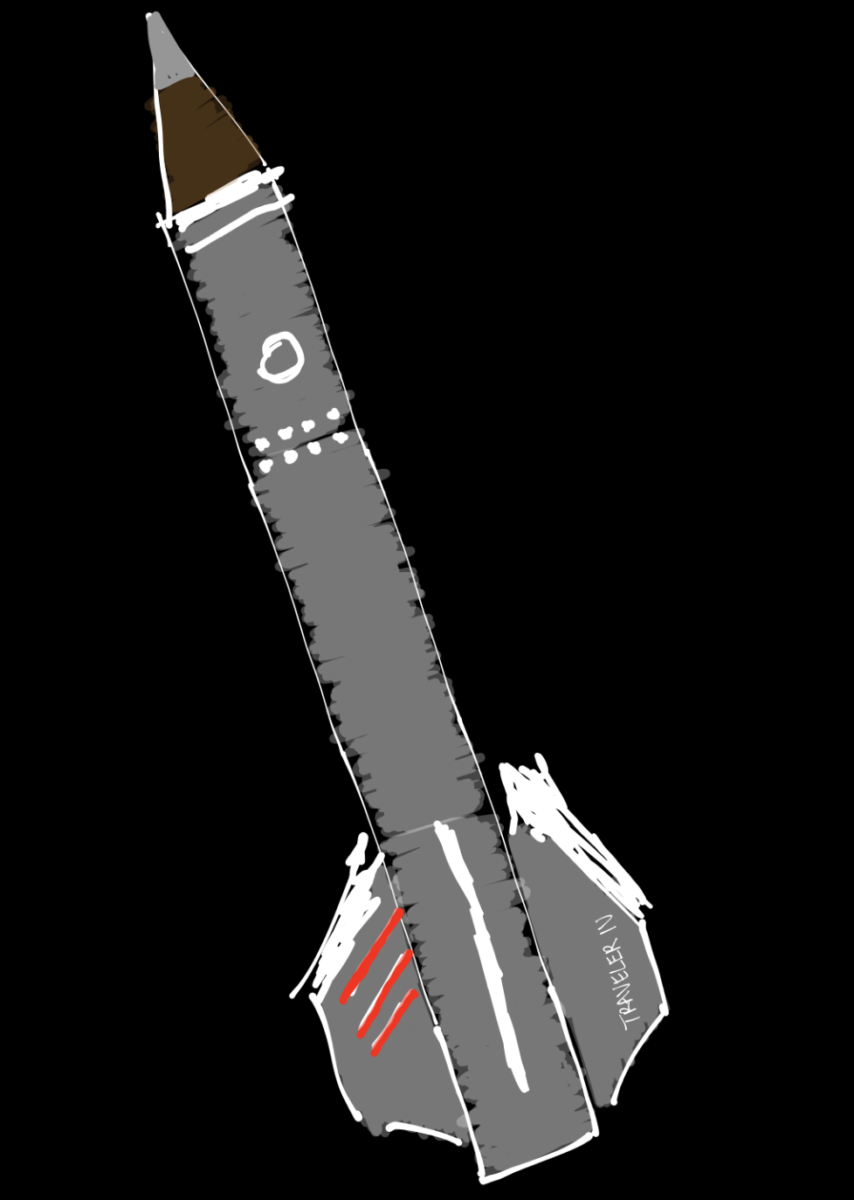

Photo credit: (Heran Mamo/Neon)

7:18 a.m., April 21: It’s T-21 minutes until Traveler IV becomes the first entirely student-designed and -built rocket to enter space, and the launch area is filled with a deafening silence. There are a handful of lead team members of the USC Rocket Propulsion Laboratory who can still talk to each other using walkie talkies as they conduct the launch they’ve been perfecting since their 3:30 a.m. wake-up call. The remaining 100 or so student members, friends, parents and photographers remain antsy, as they fumble around on a singular set of bleachers on the rocky ground of Spaceport America’s launch site near Truth or Consequences, New Mexico. There’s a lot of quirks to where RPL has been planning this world record-breaking rocket launch, partly due to the city (previously named Hot Springs) being renamed after Ralph Edward’s radio and TV game show “Truth or Consequences.” And the fact that there’s a bleacher stand in the middle of the desert.

The countdown has been reduced to T-2 minutes, and RPL alumni doubt the accuracy of the clock, because time is flying by and the anticipation is rising just like the hairs on the back of everyone’s necks. It feels like we’re watching a high school championship football game, and the seconds are counting down to the biggest winning touchdown of the team’s career. It feels like I’ve been watching for the last four years, because I’ve seen four of my oldest college friends grow from starry-eyed freshmen to senior leaders.

At T-10 seconds, we tap our phone screens at each number senior lab lead Dennis Smalling reads aloud, recording what could be the peak of lab – having a vehicle fly above 328,000 feet in the sky, where the Karman line determines the distinction between Earth’s atmosphere and outer space. What follows this countdown determines if USC RPL achieves everything they’ve set out to do since its inception in 2004.

WINNING THE SPACE RACE

After conducting an internal analysis report, USC RPL announced today Traveler IV became the first student-designed and -built rocket to soar past the Karman line and into space at an altitude of 339,800 feet with 90% certainty. Traveler IV tops off the “quiet, intense space race that has kept the world’s top engineering colleges locked in competition for over a decade,” as written in the press release. Some of those colleges include MIT and UCSD in the U.S., and Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands and University of Stuttgart in Germany.

“We lit the candle. We went up. We broke through the sky. This has been literally, quite potentially, the culmination of the goal of the founding of this lab,” said Ava Badii, sophomore recovery team member. “And to be a part of that, to know that I’ve had my hands on flight hardware, and to know that I was there with recovery, with casting, while making the igniter,… and being a part of a team knowing that we could push forward… to make something that was bigger than the sum of all of its parts is fantastic.”

Photo courtesy USC Rocket Propulsion Laboratory

And that push forward to win the collegiate space race has come after 15 years of trials and tribulations, as Traveler IV follows 21 launched vehicles and three space shot failures in lab history. Before this rocket, Traveler III launched from Black Rock Desert, Nevada on September 29, 2018, and “[f]rom a visual inspection during flight, Traveler III appeared to work as intended,” according to the launch overview page on the RPL website. Yet there was no proof it went to space: The avionics system, which is the electronic system within the vehicle, was not armed and “Go Pro cameras were shattered upon impact, which resulted in a lack of data about the flight,” according to the overview.

But this inconclusive launch from last fall did not dissuade RPL’s current members from setting out to do the same thing all over again: design and build a similar rocket and coordinate a launch date with the Federal Aviation Administration, which clears airspace for amateur rocketry groups such as USC RPL to legally launch from their approved sites, including Spaceport America and Black Rock Desert where RPL has been traveling to for years. However, the most recent and longest government shutdown in modern history, from December 22, 2018 to January 25, 2019, postponed the organization’s plan to launch Traveler IV. Nevertheless, during the weekend of April 21, 2019, I traveled to Truth or Consequences, New Mexico with lab members from USC’s campus to watch what feels like 15 years of hard work, but is rather six month’s worth of work on this specific vehicle, come to fruition.

[ezcol_2third]

REHEARSAL DAY

11:21 a.m., April 19: The over 80 members of lab bustle around the launch area to prepare for the rehearsal later today, setting up ignition cables in the thicket of barren bushes that stretch from the campsite to the launch tower 1000 feet away and transporting the rocket from the portable trailer to the on-site trailer, where the avionics team will be stationed. Upon arrival at around 8 a.m., a group of cows greet the student engineers, both flocks eyeing each other in confusion and amazement. But junior lead infrastructure officer Max Donovan feels neither by the afternoon – he’s nervous about the vehicle’s performance tomorrow. “I know that rocket inside and out,” he says. “Just give it low odds – 30%.” To intimately know a project you’ve worked on for six months during your college career and still not fully believe it can accomplish what you want it to speaks to the ambivalence surrounding every vehicle RPL has manufactured, especially if its intended purpose is to do something no other college organization has accomplished before.

However, Spaceport America already inhabits the feeling of triumph for RPL members: The last time this group traveled there was in March 2017, when Fathom II flew to 144,000 feet, setting the previous world record for the highest altitude reached by a rocket completely designed and built by students. And that triumph fuels the freshmen’s enthusiasm during this trip.

“To see something that I touched and worked on go to space” is what freshman member Cassi Kelchner says about her hopes for the weekend. She’s been excited about this “badass” organization since a member of lab brought one of the rockets into ASTE 101L: Introduction to Astronautics and talked to the freshmen class about joining lab. Now with every other member, she wears that pride on her sleeve – quite literally. Printed on the sleeve of everyone’s designated Traveler IV launch T-shirt is the team’s long-standing motto “Space or nothing.”

[/ezcol_2third]

[ezcol_1third_end class=”border”]

“Space or nothing” origin story

A few years ago, USC RPL originally wanted to launch Traveler I at BALLS, “a huge amateur rocketry event held every fall in Black Rock,” according to Smalling. But the event organizers told RPL members they weren’t allowed to launch to space. To aim for an altitude less than the Karman line, the students debated ballasting, which Smalling described as “the process of deliberately adding mass to your rocket,” which can purposefully make the rocket reach a lower altitude. RPL was going to add weight to the rocket’s nosecone to qualify for BALLS, until one member rejected the notion: “No, space or nothing.” One of the member’s fathers heard this saying and made “Space or nothing” bumper stickers for the actual Traveler I launch in 2013 at Black Rock Desert, which was the world’s first collegiate space shot attempt, according to the launch overview page.

[/ezcol_1third_end]

PROTOCOL PRESSURE

“This is the cap of my senior year,” senior lead propulsion engineer Kaustubh Vinchure said. He felt confident in the engineering behind Traveler IV – and Traveler III because there’s “nothing fundamentally different” about the two vehicles, according to him – but it’s communication that became an issue last time and a tremendous focus this time around.

An extremely crucial, detailed launch script was in order after a miscommunication issue occurred last fall between members at the launch tower and those at the avionics tent, which launched Traveler III without the avionics package being armed and no data being recovered.

But this time around, a problem clearing the airspace forced USC RPL to scrub their launch and postpone for the next day. These students couldn’t seem to catch a break before they got the biggest break in their amateur careers as rocket scientists.

[ezcol_1third]

height: 13 ft. diameter: 8 in. weight: ~300 lbs. altitude: 339,800 ft. top speed: 3,386 mph

[/ezcol_1third]

[ezcol_2third_end]

LOOKING UP AND FORWARD

Getting to space was all these students ever thought about. A dream come true, a goal reached, a mission accomplished. The emotions from T-10 seconds to T+2 minutes wavered from worry to excitement to doubt to pure elation, because “space or nothing” wasn’t for nothing after all. Even as “the waiting game” continued, which senior lead research and development engineer Kancāns described as the hours-turned-weeks of standing by to confirm Traveler IV’s altitude, the tears streaming down as the rocket flew up captured what it felt like for these students to finally, no longer just hopefully, make it to space.

Fortunately, an intact, charcoal Traveler IV was recovered after hours of its flight. It currently hangs with its predecessors from the ceiling of lab, a constant reminder to the next generations of what can be done here.

“At my age, it’s not something I would’ve imagined,” said 19-year-old freshman RPL member Dimitri Gianousopoulos. He was introduced to lab when he saw Donovan explain RPL at the involvement fair last fall, and Gianousopoulos joined the following Monday. “My question is, ‘What’s next?’”

Younger members of lab, including freshman Cori Poole and sophomore Laurence Diarra, have hinted at working on a liquid-fueled rocket that’s built differently than the solid propellant-based rockets USC RPL is used to. Diarra explained liquid rockets work by having atomized liquid and oxidizer react with each other in a combustion chamber to produce hot, high-pressure gas that when released, provides a thrust for the rocket.

“It’s good to pass it on to all the young people we have in lab,” said Lester, senior co-lead composites engineer. “They’ve been doing great work, and I’m excited to see what they do.”

[/ezcol_2third_end]