The “Despacito” remix pushes Latin music forward

By Heran Mamo | December 2, 2018

[ezcol_1half]

[/ezcol_1half]

[ezcol_1half_end]

Before you remember the first time you ever got lost in the infectious rhythm of “Despacito,” think about these two questions: Do you know that “Despacito” represents the reggaeton genre originally from Puerto Rico? Which rendition of “Despacito” are you even thinking about, the original song or the remix with Justin Bieber?

Knowing your answers to these questions will help you understand the culture that both versions of “Despacito” represent, since you probably added the Spanish-language hit to all of your pregame and dance playlists. Songs that employ various cultural elements need to be produced intentionally for putting that spotlight on those cultures and its propagators, not on the American pop stars who help those songs cross over to the mainstream music scene. For you music lovers, American artists have the power to expose you to these different cultures around the world, a supplement to your constant desire for new music. But if these pop stars fail to record these songs with respect to the cultures they’re using as influences, then they’re not giving credit where it’s due and hurting listeners by not teaching you more about different music styles around the world you might look into later and like.

My series, “Where’s That Song From,” examines the motivations of popular songs featuring white artists or remixed by white DJs that either implement different cultural sounds and musical styles or are originally recorded by U.S. regional and international artists. Exploiting these cultural musical influences that an artist isn’t associated with, especially to boost their own popularity, is cultural appropriation. But genuine collaboration between American and international artists and appreciation of the different cultures used in a production fall under cross-cultural artists and repertoire. (A&R is a sector of the music industry responsible for scouting talent and forging relationships between singers and songwriters.) This article specifically tackles the “Despacito” case, questioning whether the remix version featuring Bieber exemplifies cultural appropriation or cross-cultural A&R.

The original track by Puerto Rican singer Luis Fonsi and rapper Daddy Yankee was released Jan. 12, 2017, featuring a Latin music powerhouse collaboration between the two artists, Panamanian songwriter Erika Ender and Colombian producers Mauricio Rengífo and Andrés Torres. Placing the Spanish lyrics over typical Latin instruments, such as the cuatro (Puerto Rican guitar) and the timbales (Cuban drums), created the pop-reggaeton vibe, according to Rengífo and Torres’ interview for Genius’ video series Deconstructed.

[/ezcol_1half_end]

[ezcol_1half]

[/ezcol_1half]

[ezcol_1half_end]

The song was popular before Bieber hopped on it. “For Latino audiences, it was already a huge song, so for us, it was kind of like, ‘OK, we’ve already seen this song, we’ve been listening to it, it’s been revamped,’” said Alana Herrera, a senior at the University of Southern California minoring in music industry. Herrera is very passionate about Latin music, and she’s currently an assistant at LCM PR Inc., a public relations and social media marketing company focused on Latin entertainment.

Reggaeton, the genre “Despacito” falls under, is super catchy and easy to dance to. That’s important to consider when you’re listening to the song, because when your mouth stumbles on the Spanish lyrics, your body feels the natural groove without skipping a beat. It’s no surprise that Bieber loved the original track when he first heard it in a nightclub in Colombia. Within a few days, he was in the studio recording the remix that was released April 17, 2017.

What Bieber spun with his American pop star charm became the first №1 song on the Billboard Hot 100 for 16 consecutive weeks starting May 27, 2017. It jumped around the chart for 52 weeks, sustaining a full-year celebration of the crossover hit. Additionally, the “Despacito” remix became the first №1 song mostly in Spanish since Los Del Río’s “Macarena (Bayside Boys Remix)” in 1996. But it’s still just a remix.

“I think for a lot of America, it was just kind of like a Justin Bieber song that these then two Latino artists just happen to be on, and I think that that’s where the issue kind of overlaps,” Herrera said. She’s not surprised this version blew up the way it did (“it’s clearly a banger”), but she doesn’t agree with how much recognition Bieber deserved for the success of “Despacito.”

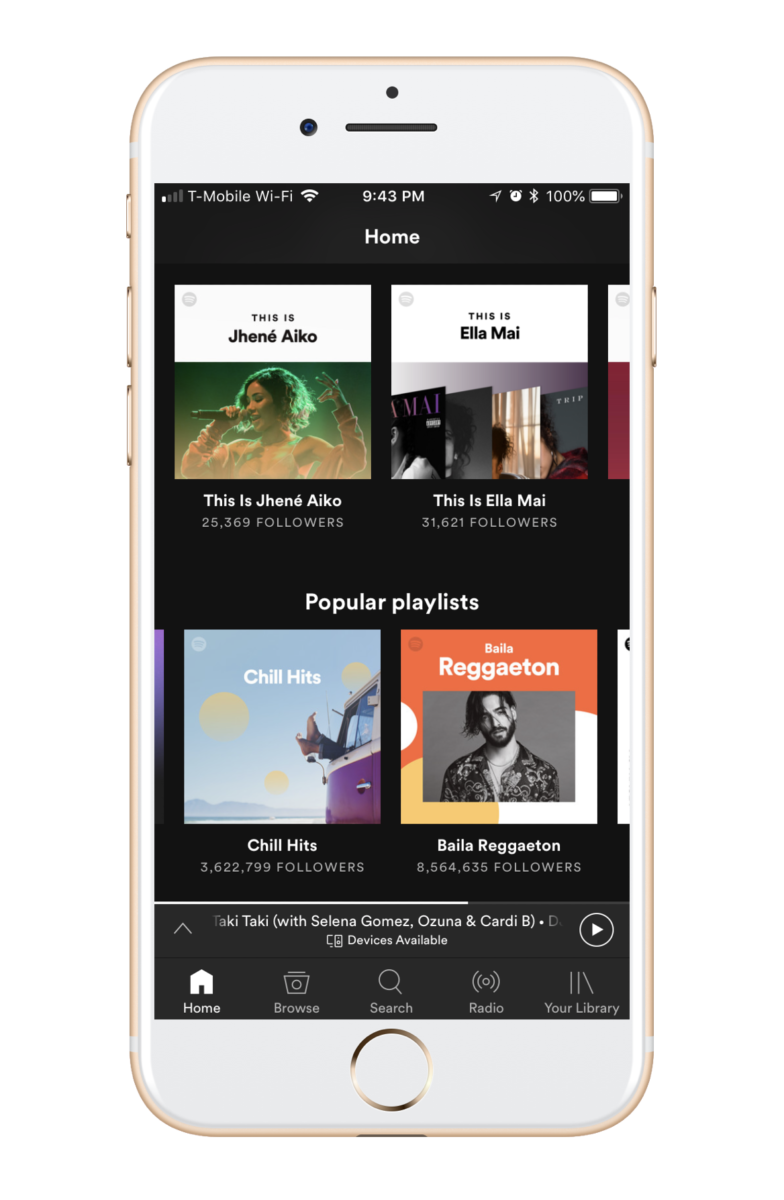

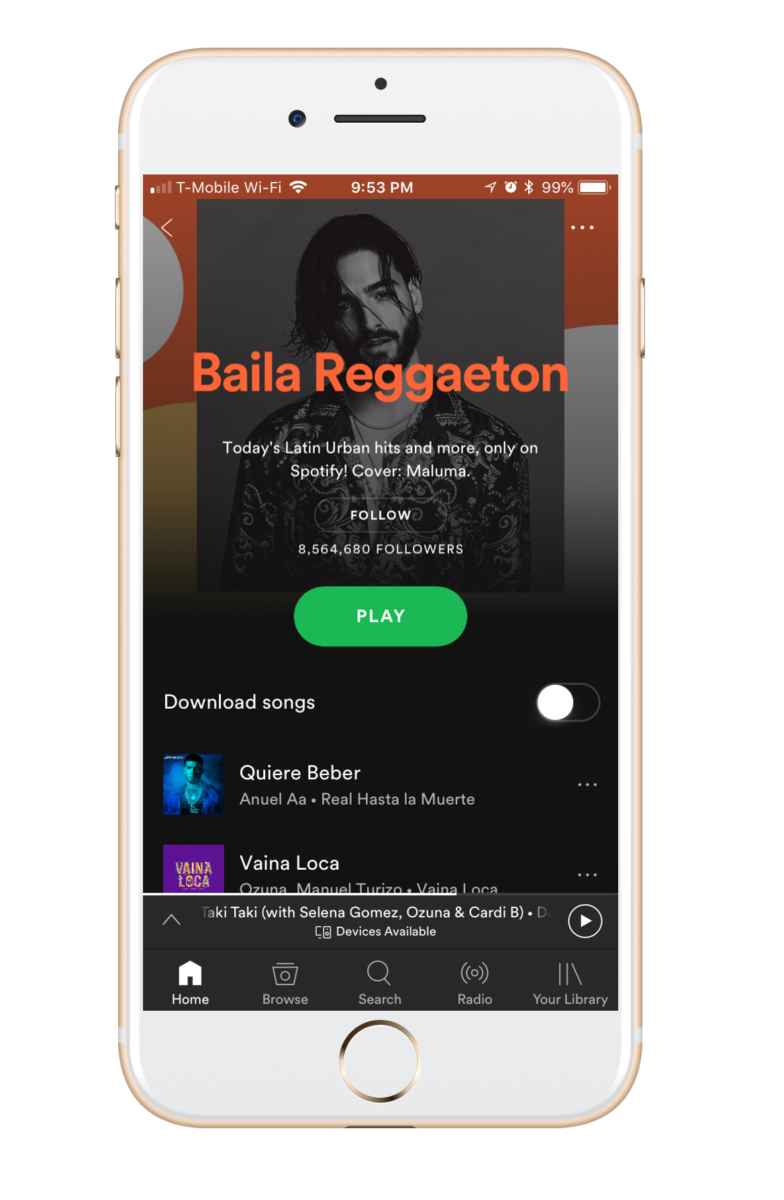

It wasn’t just Bieber who helped make the song a hit: Spotify and YouTube definitely played their roles. A Latin pop song, such as the original “Despacito,” makes its way into the hearts and ears of American audiences because these streaming and viewing platforms continuously plug global music. Spotify and YouTube help determine which popular songs make it on the Billboard Hot 100 chart; it’s not just about what’s being played on American Top 40 radio. When I opened the Spotify mobile app the week starting Oct. 7 to check out the popular playlists curated by the streaming service, the fourth playlist was titled “Baila Reggaeton” and featured Colombian reggaeton singer Maluma on the cover. YouTube also spreads Latin music around the world through its weekly music chart, as over one-third of the tracks on the chart are by Latin artists, according to Forbes.

While the “Baila Reggaeton” playlist actually featured a reggaeton artist, Herrera recalled seeing Bieber on the cover of another Latin music playlist Spotify curates after the remix made waves. That cover creates controversy because it empowers Bieber by crediting him as the vessel that brought “Despacito” into mainstream pop music, disregarding the Latino artists who created it. And for Latin music fans, especially for members of the Latinx community who see their culture being represented, it’s insulting. “It was like, ‘OK, I get it. He was an influential part of making the song where it was,’” Herrera said. “Seeing that… cover for me was just one of those things that was completely diminishing all the work that had gone on beforehand, because the reason that song was so big wasn’t purely because of Justin Bieber.”

He’s not the only major American pop star to initiate this cultural crossover power for a song: Beyoncé teamed up with J Balvin and Willy William on the remix for “Mi Gente” in September 2017, following the “Despacito” remix. American superstars maneuvering bilingually through existing Latin pop hits have to understand the blurred line between stealing a moment specific to a culture they don’t identify with and appreciating a moment by meaningfully contributing to it. What Beyoncé and Bieber do to stay on the right side of the line is involve people affiliated with and knowledgeable about the culture — specifically the language — in the production for those remixes.

[/ezcol_1half_end]

For these major artists, it’s easy to hop on something their trained ears know is a hit. Caring about how to sing in Spanish is what makes the process more challenging, because it’s not their native and/or cultural languages. And recklessly messing up the lyrics communicates negligence toward the cultural production. Rengífo told Billboard that for another American pop star, Demi Lovato, having a trained ear and feeling invested while recording “Échame la Culpa” with Fonsi made the track more authentic. “It typically takes us an hour and a half to record vocals,” he said. “It took her twice that.”

“I don’t think it makes the song less authentic by who jumps on it,” said Taeko Saito, the vice president of international A&R at Downtown Music Publishing in New York. “I think Justin Bieber has proven that he likes to jump on stuff, because he thinks it’s catchy, or he thinks it’s going to be a hit…. Now authenticity to reggaeton and Latin music… I think that’s a fine line because where do you draw the line where it starts becoming less authentic?”

Saito’s role as an A&R expert extends to connecting international singers and songwriters with American talent, which Billboard highlighted about her in a music business feature from June 2018. She shifted the question of whether a certain song’s production is authentic to a conversation about that song’s ability to bring awareness to musical styles akin to different cultures.

“Even if the question comes from a negative place, if people are having these discussions and talking about cultures and talking about diversifying music and sounds, and [a] random kid from Idaho who’s never left Idaho can go, ‘I like this song,’ that’s cool,” she said over the phone. “If that opens the door to leading that kid into listening to more diverse music from other parts of the world, I think that’s more important.”

“Despacito” helps introduce more American music listeners to reggaeton, a genre with universal, but still unexplored, appeal. I texted Katie Sullivan, a senior at USC who’s a major Belieber, and asked her if she just liked the “Despacito” remix because one of her all-time favorite artists was on it.

She didn’t just listen to the remix: Sullivan likes both versions of “Despacito”— although she’s “kinda partial to the Justin Bieber one” according to her text — and they both expose her to the reggaeton genre she hadn’t heard before. Her response echoes what Isabelia Herrera, music editor at the Latin culture news website Remezcla, hoped for following the success of the “Despacito” remix. She talked to Julianne Escobedo Shepherd, culture editor at Jezebel, about the exploitation of Latin artists in the American music industry. Isabelia Herrera took a similar stance to Saito, believing if the “Despacito” remix can create a conversation around and/or appreciation for reggaeton, then it’s not necessarily abusing Latin music.

Although Sullivan wasn’t prompted to become an expert in the genre, she was curious about its roots. And that curiosity should have triggered Bieber when he was working on the remix. Isabelia Herrera said reggaeton has embraced pop music more over the years, which creates an environment within the music industry where American pop stars can easily embrace reggaeton because it’s becoming too akin to their own territory. But that doesn’t mean these artists shouldn’t be doing their homework: “It’s a very fine line on how you decide to create this music and making sure you check in back with the culture that you’re working with,” Alana Herrera said.

Fonsi told E! News that even though he wasn’t with the “Sorry” singer when he recorded the remix, Bieber respectfully took “the time to learn the pronunciation, and more importantly, [did] the song as it was originally written.” Homework, check.

Alana Herrera hopes Latin artists, songwriters and producers of tracks that cross into mainstream American music aren’t forgotten. And hope isn’t lost for those who worked on the original “Despacito” song: Ender, one of the songwriters, became the first Latina ever to be nominated for a Grammy in the Song of the Year category in 2017, and producers Rengífo and Torres inked a major co-management deal this year with Milk & Honey, a company handling an attractive roster of American hit-makers.

And don’t forget the crazy YouTube record Fonsi and Yankee broke with the music video for the original “Despacito” song: It’s the most viewed YouTube video ever with over 5 billion views. You’ll contribute to the tally by clicking on it below. Moments like this still honor its reggaeton production.