More than a competition: The story behind Japanese American basketball in Little Tokyo

In the 1970s, a group of teenagers presented a napkin drawing of a basketball court during a Little Tokyo community meeting, where community leaders, business owners and residents were trying to brainstorm how to revive Little Tokyo. The neighborhood had a difficult time recovering from the aftermath of World War II, when Japanese Americans were sent to internment camps.

But that basketball court has never been built, until now. Relatively few Japanese Americans still live in Little Tokyo because over the years, younger generations have been pushed out by gentrification.

And yet there is an effort underway to attract Japanese Americans back to rebuild the community today.

“The group of youth told the community council that if there was a basketball court in Little Tokyo, it would bring the younger generations back,” said Adina Mori-Holt, Terasaki Budokan Development Assistant. She is referring to the teenagers that proposed the blueprint of a basketball court back in the ‘70s.

Terasaki Budokan, currently under construction, is going to be a multipurpose sports and recreational facility in Little Tokyo, replete with two indoor basketball courts.

Despite the fact many families have relocated farther away from Little Tokyo due to tides of gentrification, sports keeps these Japanese Americans closer throughout Los Angeles.

“If you are a Japanese American and grew up in LA, usually the grandparents would have the local newspaper there, but our generation would just read the sports section,” Mori-Holt said.

Japanese Americans gravitate toward baseball, martial arts and volleyball, but the popularity of basketball is incomparable. In Gardena, which had the highest percentage of Japanese Americans in California in 2010, many are excited about the ongoing Budokan project in Little Tokyo.

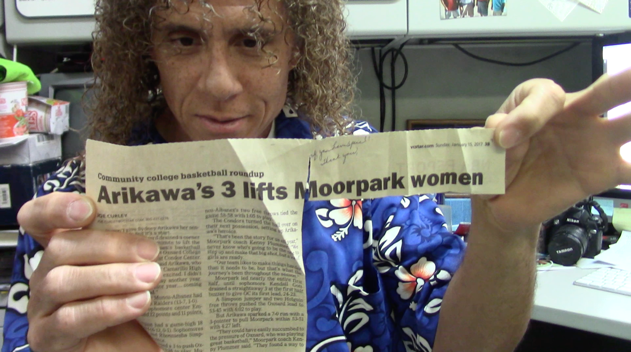

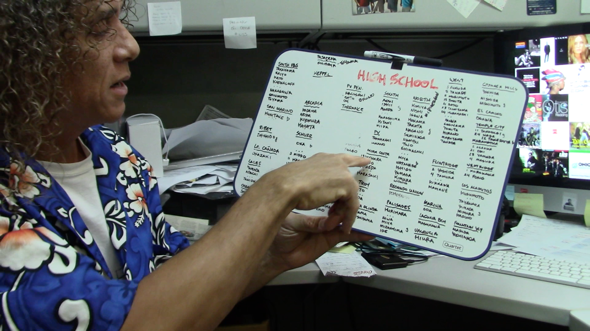

Yuko Yamauchi, the executive director of the Okinawa Association of America in Gardena, said that people in her neighborhood are crazy about the high school basketball rivalry. “In the basketball season, you will hear our community discussing the scores all the time,” Yamauchi said. Pulling out the Rafu Shimpo, a Japanese-American language newspaper based in Little Tokyo since 1903, she said the newspaper covers basketball on its front page and leaves little space for hard news.

“Most of my childhood was surrounded by basketball, and it was literally basketball every single weekend,” said Manami Hayashi, a junior at Flintridge Sacred Heart Academy who started playing basketball since she was 5 years old. “Basketball never stops.”

Kim Kawasaki, the Terasaki Budokan Community Gifts Manager, has also been playing basketball in the Japanese American leagues since she was 5 years old. “If you find any Japanese Americans today, either they play basketball, or their parents play basketball, or they know somebody who plays basketball, or they are scorekeepers,” she said.

After playing in Japanese American basketball leagues for more than 30 years, Kawasaki said her old basketball team became her core group of friends that she still sees today. “I have friends all over Southern California, and basketball is the reason why, because I probably grew up playing against or with them,” she said.

Her stories of basketball led to her seven-year commitment to the Budokan project. “It started off as a concept when the teenagers pulled out a napkin, drew a gym and said, ‘You build this, people will come,’” she said.

Kawasaki said the project was suspended in the ‘70s because people could not find a site for the gym. The Budokan project broke ground in 2018 and is expected to open in early 2020. “This project for me personally struck a chord. I grew up in sports, I know the opportunities it provided for me. I want to carry that through for the future generations,” she said. “We really want to bring younger generations back into Little Tokyo. With all the gentrification that is going on in the area, we want to make sure that there’s something here that’s permanent for the next fifty years.”

The project also represents the determination of the Japanese American community, which has watched the demise of other ethnic enclaves in Los Angeles, and its continued survival. “In today’s political climate, we want the Budokan to be a welcoming place for all people visiting Little Tokyo, to share our JA roots in sports and to encourage visitors to learn about the JA experience during World War II so that horrible trauma never happens again,” Mori-Holt said.

Pictured: Kim Kawasaki at the Budokan construction site in Little Tokyo